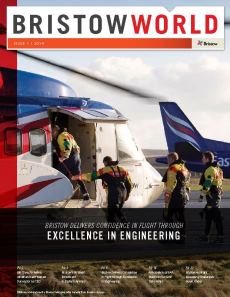

Bristow Delivers Confidence in Flight Through Excellence in Engineering

Bristow helicopters fly under some of the most challenging conditions in the world. In harsh climates with unrelenting heat and unbearable cold. Over gritty desert sand, corrosive sea water and fiercely blowing snow. Across treacherous terrain and long stretches of open water where landing just isn't possible. Precision performance of the aircraft is critical.

Whether flying conditions are extreme or simply routine, crews and passengers on a Bristow helicopter are dependent upon the precision performance of the aircraft. To ensure everyone's safety, as well as peak availability and operating performance of the machine, each and every aircraft we fly needs frequent and infallible maintenance.

The technical skills and knowledge of maintenance and engineering are a crucial part of Bristow’s business. They are what keeps our aircraft airworthy and serviceable – and above all, safe. They allow Bristow to meet the specific needs of our customers and business units in terms of aircraft configurations and flying schedules. Quite literally, Bristow could not fly without the superior work of our technical professionals.

Bristow has nearly 500 aircraft located around the globe with a total fleet as large as those operated by some commercial airlines. Our helicopters and their associated inventory of spare parts represent the biggest capital expenditure of the company. An extensive maintenance program protects our investment in these intricately technical machines and keeps them at the ready to serve our customers.

Even before a helicopter rolls off the manufacturing line and we take delivery, Bristow engineers are involved with the machine’s design and features. Our technical support program spans from the cradle (and almost conception) to retirement, overseeing every aspect of how the aircraft is maintained until we no longer own or operate it.

The maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) of helicopters is a highly regulated business. Civil aviation authorities in various countries and regions set the standards for how the work must be done – and in all cases Bristow meets or exceeds the local regulations. In fact, some of our contributions to helicopter engineering and design have actually set the bar higher for safety standards and regulations. For example, the Integrated Health and Usage Monitoring System (IHUMS) developed by Bristow engineers has become a required safety feature in all UK-registered offshore transportation helicopters.

The people who maintain aircraft in a safe and airworthy condition are the backbone of aviation. Approximately one-third of Bristow’s workforce reports to our maintenance and engineering organizations around the globe. Here we get to know what these people do and how their dedication and excellence in engineering contribute to Bristow’s overall success.

Global Capabilities with Local Operations

With Bristow having operations all around the world, it’s imperative that we sustain the same high levels of maintenance capabilities regardless of how remote the location may be. Typically we perform two levels of work on our helicopters: routine or line maintenance, and heavy maintenance.

Executed by the individual business units, line maintenance is something fairly standard that can be performed on operational aircraft in a matter of hours or days. This would include something that is routinely planned, such as a periodic inspection, or some type of minor unplanned repair, such as replacing a component that has been damaged. These activities can usually be done at local or regional bases.

Heavy maintenance is an extensive repair or even a complete overhaul (called a “D check”). This type of service is usually done by the Central Operating Business Unit (COBU) every four to six years – it’s based on flying hours – in Aberdeen, Scotland, or New Iberia, Louisiana, in the United States, although other facilities can provide heavy maintenance as needed. For a D check, the aircraft is disassembled and taken down to the bare airframe and refreshed from nose to tail. The aircraft is down for weeks or months for this major overhaul and comes out at the end like a new machine.

The heavy maintenance facilities also house various workshops that provide support functions. For example, in Aberdeen there is a mechanical workshop, an avionics workshop, a safety equipment workshop and a composite workshop. We have the capability to refurbish parts to restore them to a condition ready for use in an aircraft again, and the engineers can install modifications for the helicopters when required. Spare parts are kept in the stores and workshops to be ready when needed.

As you can imagine, it takes a lot of precise coordination to get all the people, parts, documentation and aircraft together at the right time, in the right place, for the right work – all the while minimizing downtime and inconvenience for our customers.

Regulatory Oversight

Virtually every aspect of MRO is highly regulated by local civil aviation authorities to ensure the safety of everyone transported aboard our aircraft. Among others, just a few of the numerous government authorities that oversee our work include the Civil Aviation Safety Authority in Australia, National Civil Aviation Agency of Brazil, European Aviation Safety Agency, Nigerian Civil Aviation Authority, Civil Aviation Authority of Norway, Civil Aviation Authority of the United Kingdom and Federal Aviation Administration of the United States.

The engineers and technicians who perform certain aspects of the maintenance work must be licensed by their local civil aviation authority. It’s quite a rigorous process to become licensed. A mechanic applying for a license typically must have many years of technical education, hands-on experience in a supervised environment and passing grades on a series of exams.

A license is only good in its country of origin, meaning that someone who is licensed in the UK cannot move to the U.S. and immediately begin work; he must become licensed by the U.S. authority as well. This makes it challenging for Bristow to move people around from country to country and requires forethought about staffing when we are opening maintenance facilities in a new location.

A licensed engineer carries heavy responsibility. When he has completed a work assignment, his signature on a Certificate of Release to Service document certifies the airworthiness of the aircraft. He can be held criminally liable if his actions contribute to, or result in, an incident.

Configuration Control

In the helicopter transport industry today, a helicopter manufacturer delivers an aircraft, and the operator customizes and configures it to suit its specific needs. Those needs can be global or regional, and they certainly are mission or task specific, such as search and rescue (SAR), offshore transportation or training. Clients also can specify certain configurations for the aircraft dedicated to their contracts.

Every aspect of a helicopter’s configuration is tracked in detail. We must know precisely what components are on the aircraft, where they came from, and how they have been serviced and maintained. Bristow’s global and regional Configuration Control and Supply Chain groups help with tracking this information, which is needed for regulatory purposes and also for our own knowledge.

Danie Lordan is a Fleet Engineering Specialist and the Business Process Owner (BPO) for Configuration Control in Aberdeen. He notes that document management is an important part of his team’s work. “We have Bristow-generated documents and others from the manufacturer that instruct the technician precisely what should be done to maintain and service a specific aircraft. There are Airworthiness Directives (ADs) and Alert Service Bulletins (ASBs), which can change frequently, and it’s the job of Configuration Control to ensure our people are working with the absolute latest versions,” says Lordan.

The regulatory agencies that oversee aviation MRO require that companies like Bristow maintain an audit trail of reference documents that have been used for maintenance work orders. According to Lordan, “If an incident were to occur, the regulators would want to know precisely which documents were used to direct the work done by the technician. The engineer signs off on the work he performs and is responsible for using the most up-to-date documentation available.”

This is one area that is expected to benefit from processes built into SAP once it goes live later this year. “We plan to use SAP to give the maintenance staff everything they need,” says Lordan. “They can be sure that everything they use to do their job is to the latest and greatest revision and standard. And rather than having the maintenance person go collect that data by himself, we will put everything out for him so that all he has to do is familiarize himself with the latest revision to go do the job.” Lordan says this will save significant time for the engineer and help him be more productive.

Also under the purview of Configuration Control is the award-winning Design Office based in Redhill in the UK. This exceptional group develops modifications for our helicopter fleet as well as for external customers. The Design Office has a long history of innovation dating back to the earliest days of Bristow Helicopters and is recognized for industry-leading innovations that have become the new benchmarks for safety in this industry.

Design disciplines include avionics, mechanical installation, structures, stress analysis and full technical publications. This comprehensive capability allows us to offer complete service, from concept through all stages of design, manufacture, installation, test and certification.

The combination of our design capability and long experience with providing 24-hour SAR helicopter services uniquely qualifies Bristow as the world leader in creating modifications for this specialist activity, from providing forward-looking infrared (FLIR) installations to aid with searching in low visibility conditions to a complete package including auto-hover, rescue and survival equipment.

“These designs are our intellectual property, so they belong to Bristow,” says Paul Nouch, Head of Design. “We apply to the regulatory authorities for an approval for these modifications, which certifies that they are airworthy. Given that we are a global company, our primary approval is based in Europe, so all of the things that we do are EASA (European Aviation Safety Agency) approved; through a bilateral agreement we can get them FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) approved in the United States. Our design organization based in the UK also holds CASA (Civil Aviation Safety Authority) approval for Australia, so we can get these modifications approved in Europe, the United States and Australia. From there we pretty much cover most regulatory authority requirements. We might need some negotiation in other parts of the world, but if we have had a modification accepted in those three areas, we can generally get it accepted anywhere else.”

Maintenance Planning and Execution

“It takes a lot of forethought and planning to optimize our maintenance resources and minimize the downtime of aircraft. We have teams at both the global and the local levels that do maintenance planning,” says Ben Reed, Global Maintenance Planning Manager. “Basically we forecast when maintenance is going to be due and send schedules out to the business units. We plan for the parts and put a lot of pieces in place to execute the maintenance,” he continues. “We want to get to the point where planning is done more globally so the local engineers can concentrate more on the work at hand rather than planning for the next upcoming activity. SAP will help us quite a bit in consolidating the planning at the global level.”

Maintenance planning is complicated by the fact that we operate under so many different regulatory authorities. According to Reed, “Each business unit answers to the authorities overseeing that country. Our International Business Unit (IBU) works under several authorities. Not only is our work dictated by different rules, but we also have to contend with the differences in equipment from one location to the next. We’re going through the process now of trying to standardize this as much as possible. Ninety percent of the requirements across all our maintenance organizations are the same, so we spend a lot of time on the remaining 10 percent. We believe that SAP will really help us to drive consistency in the way we approach maintenance planning.”

Reed says that Bristow’s Target Zero program has had quite an impact on maintenance workers over the years. “Target Zero has been around for six or seven years now, and it has really improved the way we work. For example, from a personal protective equipment (PPE) perspective, our guys are all cognizant of the need to wear safety shoes, eye protection and a helmet if they are going to be working from heights. Target Zero also gives us the right to slow things down or stop work completely if we see that something isn’t right. We don’t let schedules override safety.”

Training for the Future

With Bristow’s organic growth and the expansion of our fleet, there’s a need to bring new people into the maintenance organization. John Cloggie, Vice President and Chief Technical Officer, is credited with rekindling the company’s apprenticeship program back in 2005. According to Cloggie, “There are apprenticeship programs today in Australia, Nigeria and the UK. My experience has been predominantly in the UK, where we started the first program in late 2005 and have taken on eight apprentices a year since then in Europe. In September 2013 we increased that to 20 because we want to train people from around the UK for Bristow’s UK SAR organization. At this early stage before we move to full service SAR delivery, we are putting personnel through a full year training program, at the end of which they’ll be licensed aircraft engineers and will certify for their own work.”

With maintenance as a global activity, one might expect that each engineer would conduct his work in his native language. Not so, says Engineering Manager Tim Dobbs. “English is the language of the aviation world, so to speak. Right now everything we do is essentially in English. The maintenance manuals are in English, the technical documents, the bulletins, and so on. I’ve known people that are not native English speakers who learn the technical part of it without necessarily having the conversational aspect of the language.”

Dobbs says that SAP can support multiple languages if the company ever chooses to go that way. “It is not a concern for the moment, but that is something we can look at as we do expand. Nevertheless the technical information will still be in English.”

Supply Chain Management to Avoid Downtime

Helicopter components are subjected to some of the most demanding conditions and they are regularly replaced to prevent failure during flight. Angus Kerr is the Global Supply Chain Director. His team works closely with the maintenance planning technicians to understand upcoming needs for parts.

“Supply Chain is responsible for providing purchasing, leasing, renting and provisioning of parts to meet planned and unplanned requirements,” says Kerr. “The planned requirements exist because we know you can fly an engine for only 5,000 hours before you have to change it. So we know, for example, that in another 1,000 hours we are going to have to put in a new engine, because this aircraft has already flown 4,000 hours. Supply Chain is responsible for that planned provisioning of engine components at the right time, at the right place.

“We hold stock and we have an equipment stock system around the world to meet the unplanned requirements,” continues Kerr. “We have three hubs – soon to be four – where we keep the bulk of our parts: New Iberia, Aberdeen, Perth and one coming on in Lagos. Radiating out from those hubs are bases that we call spokes. We keep a smaller supply of parts at these bases for line maintenance. In total, Bristow keeps hundreds of millions of dollars in parts inventory throughout our hubs and spokes. The intent is to make sure that aircraft aren’t kept out of service waiting for parts, especially for unplanned maintenance.”

“Over the next few years, Bristow will begin to have manufacturers hold the parts in stock for us on consignment as we transition the fleet,” says Kerr. “This will vastly reduce the amount of inventory we buy and stock ourselves, although we’ll still keep smaller local inventories to make sure we always have what we need on hand.”

“The main thing about Bristow’s operations is the focus on safety,” says Kerr. “Supply Chain contributes to that safety by ensuring that all the parts we use have certification. When we receive a part, a goods-in quality inspector reviews it against the requirements to make sure that it is the right part. We ensure that the parts that we use are only high quality, fit-for-purpose parts as approved by the manufacturer. We maintain that process all the way through, so when a part is kept on a shelf, it has certification so that it is traceable. When it is fitted to an aircraft, it is still traceable. It is the final responsibility of the engineer to ensure that the part he is fitting to that aircraft is the right part and is suitable and is serviceable.”

Mark Becker, Director of Central Operations, focuses on service delivery for Supply Chain. Becker explains that Bristow recently set up an Aircraft on Ground (AOG) group that supports the regional business units 24x7, 365 days a year. “Any part that is going to keep an aircraft grounded, we start sourcing that part to get it as soon as possible. This is especially important as we transition to the model of using the manufacturers as our main source.”

SAP will have a huge impact on Supply Chain processes, according to Becker. “SAP is going to provide us with more automated tracking of what we need, what we use, where parts are, and where parts need to be. This will help us reduce excess and dormant inventory and be more efficient in planning and purchasing.”

Fleet Management, Support Through the Aircraft's Life Span

Bristow now has an office dedicated to global fleet management headed by Nina Jonsson, Global Director of Fleet Management. Jonsson was recruited for her many years of experience in the fixed-wing world where fleet management is crucial. Jonsson explains: “Our group handles the fleet globally and looks at it holistically. We buy the aircraft; we oversee the configuration of the aircraft and how we want to modify them as well as how we want to standardize them across the globe. When we are no longer operating them, we manage the disposal process, either by selling them, turning them back to a lessor, or parking them and possibly using them for parts. One of our major undertakings right now is to simplify our fleet,” she continues. “We are moving aggressively to as few as eight fleet types over the next five years. We already know what we’re going to be buying that will comprise our long-term fleet.” Jonsson spent her first year on the job convincing people of the benefits of reducing the fleet types in use. “If we simplify the fleet, we reduce complexity and introduce standardization. It helps us to standardize processes. It makes the aircraft more interchangeable globally, so we can move them around the world to support different contracts. We can use our workforce more productively. And it makes us better able to address any sort of tactical short-term needs because we eliminate the extra effort to support all of these different configurations and fleet types. About 20 percent of our operations have short-term tactical – and potentially large – contracts at play. We have to maintain that entrepreneurial nimbleness. If we have everything standardized, we can focus our resources more intelligently on these strategic short-term opportunities.”

Bristow now has two representatives at the manufacturers’ locations – one in Europe and the other in the U.S. Jonsson explains: “They interact with the production team on a daily basis, following aircraft on the production line to ensure the helicopters are built to our requirements and standards. These people are the face of Bristow to the manufacturer so the manufacturer doesn’t have to make 50 different phone calls to get questions answered.” Jonsson says the U.S. representative is in place at Sikorsky, but also handles the AgustaWestland facility in Philadelphia. The representative in Europe resides at AgustaWestland in Italy, but also handles Airbus Helicopters in France.

Standardization doesn’t mean Bristow is giving up features or capabilities. “We are analyzing the modifications we typically do to our aircraft all around the globe, and we are asking our manufacturers to incorporate those needs before we take delivery,” explains Jonsson. “Eventually what we want to do is just get the aircraft ready off the production line. We pick up the keys and start flying our revenue flights. It is going to take us a while to get there, but that is the effort that is under way.”

To reduce the risk of exposure to having one type of aircraft grounded for a period of time, Bristow is selecting multiple manufacturers that can deliver light, medium and heavy categories of aircraft. “We’re mindful of the recent grounding of the EC225s and the impact of taking those aircraft out of service for a while, but a situation like that is a rarity in this business,” Jonsson says. “That only happens once or twice in a lifetime. Still, we have to plan for it and mitigate our risk of a grounding.”

In 2013, a new Global Fleet Support group was created, consisting of more than 50 staff based in four locations around the world with the two central hubs in Aberdeen and New Iberia. Team members include aircraft technical specialists who support each aircraft, engine type and HUMS system, maintenance programmers and document controllers to track certification and technical records. Fleet Support reviews all incoming service bulletins (SBs) and technical documentation, while issuing technical directives and providing support on maintenance programs and reliability. Russell Gould, Head of Fleet Support, explains how the team provides technical support and ensures the continued airworthiness of the fleet. “This is the true engineering side of the business and the focal point for all technical issues,” he says. “We are a liaison to the airframe and engine manufacturers and strive to work with the manufacturers before the aircraft are in production. We’re also involved in a number of industry working groups to help provide operator feedback, which is used to develop future modifications and improved maintenance regimes.”

Bristow Culture of Safety, Training

Every major helicopter transportation services company has to perform maintenance to keep its aircraft operating safely and efficiently. Most of the tasks that must be performed are standardized due to industry regulations. It’s the Bristow people who are dedicated to what they do – going above and beyond the minimum requirements every day – that are helping Bristow on its journey toward operational excellence. Cloggie attributes it, in part, to the superior training Bristow provides its employees. “I worked for a fixed-wing company, and I worked for the three major offshore helicopter companies, and in each case Bristow exceeds the training others provide in a dramatic way,” he says.

Target Zero certainly contributes to the positive attitudes that Bristow employees are known for. Engineers know they can take the time to do the job right the first time because safety is valued above everything else. “Before I started working for Bristow,” says Lordan, “I had a chief engineer that told me something very interesting. He said, ‘If you haven’t got the time to do the job properly the first time, where will you find the time to fix the mistakes?’ That’s a very good philosophy to start off with, and Bristow people observe it every day.”

The original article appeared in Bristow World Issue 1, 2014.